Indirect Imaging, Elevators Gone Wild, Backlight Cosmology

Maps on planes, elevator regulations, urban burn liability, imaging the cosmos through backlight scans, and more!

Morning, everyone. Here are some links, thoughts, and stories. If you like what you see, please feel free to subscribe or follow, to forward to friends, or otherwise help spread the word. Thanks!

A RICH INTERIOR LIFE, OR: MEN LOOKING AT MAPS

I can no longer find the original image, as either my Googling skills have degraded over time or it’s just impossible to find older content on the internet now, but several years ago someone posted a photo on social media of a bus filled with passengers where every single person is looking down at a phone or tablet computer. They aren’t talking amongst themselves or taking in the scenery or doing anything other than staring at a screen.

There is one other passenger, however—a Golden Retriever, if memory serves—sitting alone in a window seat, looking outside with a dopey grin on its face, fur ruffling in the breeze. The caption said something like, “No one understands my rich interior life.”

This Retriever with a rich interior life came to mind last week when an absolutely idiotic series of articles began appearing online, starting with a piece in GQ about men “raw-dogging”—or “barebacking”—long-haul flights by watching nothing but the in-flight map the whole time. No films, no TV shows, no headphones or books, seemingly no distractions at all. Just geography. This was presented as so alien, so psychologically mystifying, that half a dozen other writers, including CNN’s Lilit Marcus, picked up the story as a supposedly newsworthy trend (and, of course, I am adding to the slop by posting about it here).

According to GQ’s Kate Lindsay, looking at maps while traveling by air is hyper-masculine—something only a Man’s Man could do—and if you don’t know what men are, by the way, she reminds us that we’re “the gender that brought you frat hazing and Logan Paul.” According to Gabi Conti, covering the story for a site called Betches, if a man seems interested in cartography on a plane, this should raise a “new red flag” for women. She asks tough questions about those of us who are into maps, such as, “What are you trying to prove by doing this? That you have nothing going on in your brain?” Elle’s Rebecca Mitchell followed up on the alleged trend, writing about this behavior as a “mysterious thing” men now do, something clearly intended, in her eyes, as a “heroic display” for other passengers.

It’s worth noting that these articles do not criticize fellow frequent flyers who might spend a journey reading a single long novel or listening to music on headphones; these articles specifically and only take issue with men looking at maps. Appreciating aerial views of the Earth’s surface while flying over that surface is apparently a sign of cognitive decline, if not outright psychosis, they imply, whereas rewatching a corny syrup of bad Marvel movies, or reading Elin Hilderbrand, is proof of elite-tier consciousness.

I am genuinely curious what these writers would make of the sight of silent men looking at maps for long periods of time in different architectural settings, such as a library or home office, with no music playing and no TV on in the background, just raw-dogging it, really barebacking things, maybe spinning a globe for a couple hours to see where it lands or flipping through a world atlas to get a better sense of the planet, learning about foreign borders and where obscure archipelagoes really are. “Seriously, are men okay?” Elle asks in the universally affected tone of today’s worst online writing. Looking at maps is “super creepy,” Betches agrees.

In any case, even the most basic activities associated, rightly or wrongly, with men are being exoticized as alien behaviors that allegedly no one—especially women—can understand. This has come to the point that quietly minding your own business on an airplane, exploring an interest in cartography, is considered a “red flag.” “I find this concept terrifying,” Conti writes. “What are they plotting?!”

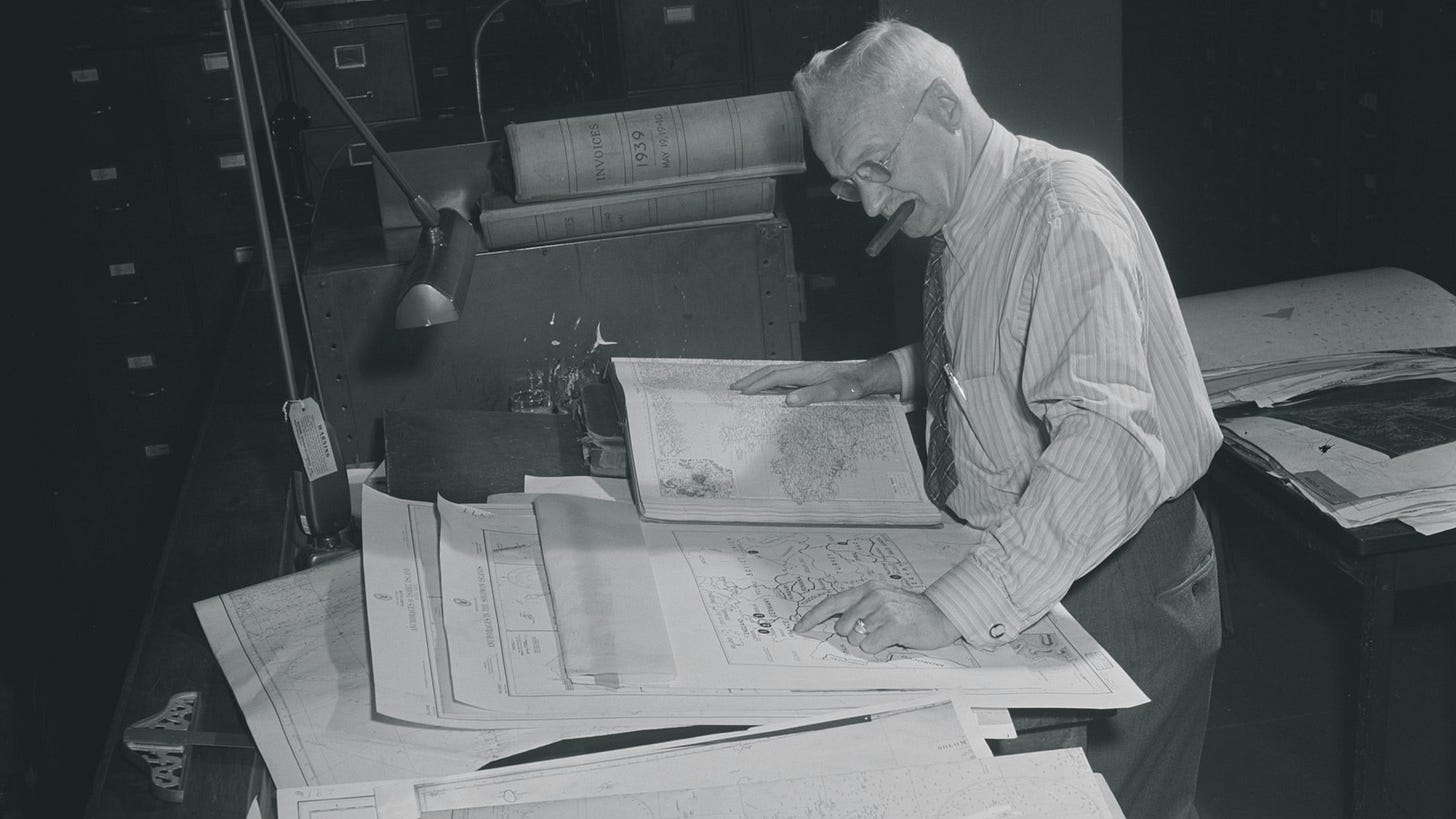

IMAGE: Ladies, look away—here is a man raw-dogging a map. “Cartographer consults key maps filed for reference in making maps for paper,” according to the U.S. Library of Congress. Major red flags.

ELEVATORS GONE WILD

In an example of quiet focus and sustained curiosity that will likely shock the previously mentioned authors, Stephen Jacob Smith wrote an op-ed for the New York Times last week about his “mission to understand the American elevator.”

Smith, who posts on X under the handle @marketurbanism, suggests that elevators are behind the soaring costs and slowing pace of U.S. construction. “Elevators in North America,” he writes, “have become over-engineered, bespoke, handcrafted and expensive pieces of equipment that are unaffordable in all the places where they are most needed. Special interests here have run wild with an outdated, inefficient, overregulated system.”

He points out how few elevators the U.S. actually has, compared to Europe—“the United States is tied for total installed devices with Italy and Spain,” nations that are orders of magnitude smaller than the United States—as well as what it costs to build and maintain elevators here. “A basic four-stop elevator costs about $158,000 in New York City,” Smith explains, “compared with about $36,000 in Switzerland. A six-stop model will set you back more than three times as much in Pennsylvania as in Belgium.”

The rest of Smith’s piece explains why. He touches on immigration and visa reform, the uniquely combative U.S. legal landscape, and other aspects of urban regulation that he convincingly argues are holding back the country’s construction market. For example:

The United States and Canada have also marooned themselves on a regulatory island for elevator parts and designs. Much of the rest of the world has settled on following European elevator standards, which have been harmonized and refined over generations. Some of these differences between American and global standards result in only minor physical differences, while others add the hassle of a separate certification process without changing the final product.

If physics is the same everywhere and there are no measurable differences in safety outcomes, why reinvent the wheel (or elevator)? America’s reputation for unbridled capitalism and a stereotype of Europe as a backwater of overregulation are often turned on their head in the construction sector.

The piece is worth reading in full. Note of caution: don’t sit there for several minutes afterward, thinking about Smith’s op-ed, if you read this on an airplane with nothing but a map on your screen. That would be super creepy.

CONTACT BURN

Asphalt-centric cities are becoming so hot that “more people are suffering serious burns from contact with hot outdoor surfaces,” the New York Times write. “For some, the burns are so extensive that they prove fatal, according to burn experts.” If you pass out from heat-stroke and fall down in a city such as Phoenix in high summer, “‘Your body just literally sits there and cooks,’ [Dr. Clifford C. Sheckter of Stanford] added. ‘When somebody finally finds you, you’re already in multisystem organ failure.’”

In an earlier post, I wrote about—and recommended—a book called Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush. Although another recent book comes to mind, one that I have not yet read—The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet by Jeff Goodell, which could very well do exactly what I’m about to describe—I’d imagine that Rush’s journalistic approach would be incredibly successful in the context of writing about urban contact burns. More specifically, Rush’s methodology for her book Rising was to ask people “to tell me their flood stories,” without getting into larger, instantly partisan arguments about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Tell me your burn stories, you could say to people living in increasingly sunburnt cities.

“‘You pass out on a surface that is burning you, and you don’t wake up,’ Mr. Steinbeck [fire chief of Clark County, Nevada] said. ‘It just keeps burning you.’ (…) Some [people burned by pavement] are diabetic and have limited sensation in their lower legs, and don’t realize their feet are burning as they walk barefoot,” the New York Times writes. It’s easy to dread what this is also doing to wild and domesticated animals, alike.

“I think to myself, ‘These patients are going to require a lot more work and a lot more extensive care than the other types of burn injuries,’ said Dr. Saquib, whose hospital has also seen admissions rise in recent years [Saquib recently moved to Las Vegas from Florida to practice medicine]. Last Thursday, about half of the 31 patients hospitalized with burns had suffered pavement burns.”

Contact burns like this are a story of infrastructure, transportation, municipal policies toward homelessness, and, in the end, atmospheric carbon, all feeding into the realization that badly-designed urban landscapes can fatally burn the creatures living there. This also reveals that, through the materials we’ve chosen and the kinds of spaces we’ve created, we unknowingly spent several generations constructing ovens in waiting, disguised as cities—and that, most likely, burn liability will become a design parameter for urban planners in the near future.

LIGHT WITHOUT, SHADOWS WITHIN

Some of the most interesting interior-mapping techniques today involve incidental views, often obtained indirectly. A few years back, I wrote about how light reflecting off of “shiny” objects can be mathematically unfolded, so to speak, to reveal what was in the room around that object at the time the photo was taken. A foil potato-chip bag, for example, a faceted champagne flute, a birthday balloon, or a round Christmas-tree ornament: place this sort of object in a room, hit it with light, record the reflections, and, after some toggling, you can “construct a rough picture of the room around it,” as Scientific American reported at the time.

Or consider “computational keyhole imaging.” “Non-line-of-sight (NLOS) imaging and tracking is an emerging technology that allows the shape or position of objects around corners or behind diffusers to be recovered from transient, time-of-flight measurements,” we read, courtesy of Stanford Computational Imaging Lab researchers. However, they add, those techniques have limits. “Here, we propose a new approach, dubbed keyhole imaging, that captures a sequence of transient measurements along a single optical path, for example, through a keyhole. Assuming that the hidden object of interest moves during the acquisition time, we effectively capture a series of time-resolved projections of the object’s shape from unknown viewpoints.”

The metaphoric—even Platonic—aspects of this are simply too good not to highlight: something we cannot approach exists in a space we cannot enter, but now this invisible, hidden, and unknowable presence can at least be glimpsed, if not modeled in its resolute entirety.

More prosaically, this technology seems to fall somewhere between avant-garde cinematography, espionage, and advanced mathematical modeling—and, from what I’ve read, it sounds like these techniques are in their Eadweard Muybridge phase. It is still very early, in other words, and we have not yet seen their full technical potential.

The indirect observation of hidden objects in distant interiors fascinates me, so I was interested to see last winter that WiFi signals bouncing around a room can also be analyzed to find and map 3D objects in that room. WiFi, of course, has been used as a burglar alarm for nearly a decade, but, with sufficient resolution, has since become a sort of remote-sensing tool for accurate 3D mapping of closed spaces—or, in the words of New Scientist, WiFi can now be used to “decode the shape of even motionless objects from the other side of walls by looking at the unique shape of their Wi-Fi reflections.”

The technique relies on the fact that when radio waves hit a sharp or tightly curved edge, they are diffracted into a very specific shape of outgoing rays known as a Keller cone. This shape can be measured and mathematically traced back to its origin, revealing the location of the point that created it.

[Yasamin Mostofi at the University of California, Santa Barbara] says that with enough Keller cones, it is possible to build up a 3D map of points along the edges of objects within a room. In tests, the team used three off-the-shelf Wi-Fitransmitters to send wireless signals into the area and recorded them using a tower of Wi-Fi receivers mounted on a remote-controlled car. The researchers used the car to move the receivers backwards and forwards, allowing them to measure reflected signals as if they had a large 2D grid receiver.

This description of the “2D grid receiver” implies to me that these sorts of tools will soon be both portable and easily deployed outside of a laboratory, useful even in unusual circumstances to “scan” inside an architectural space and to determine what exists inside. It will likely also have police uses—scanning residential homes, using those homes’ own WiFi networks, to locate a barricaded suspect or a kidnapping victim—as well as criminal implications. Roll up to a house, assess its WiFi network, then set to work analyzing shadows and reflections to find particular objects throughout the locked interior.

But I wanted to end with an example on a very different scale. There was an article in the excellent Quanta Magazine last year about “invisible cosmic structures” that are being revealed, hidden in what’s known as cosmic microwave background radiation (or CMB). CMB “continues to stream through the sky in all directions,” we read, “broadcasting a snapshot of the early universe that’s picked up by dedicated telescopes and even revealed in the static on old cathode-ray televisions.” Recall the WiFi signals we were talking about, above, that themselves stream through a particular room in all directions, and the fact that these signals can reveal objects or structures in that room.

Over the course of its nearly 14-billion-year journey, the light from the CMB has been stretched, squeezed and warped by all the matter in its way. Cosmologists are beginning to look beyond the primary fluctuations in the CMB light to the secondary imprints left by interactions with galaxies and other cosmic structures.

Now recall that reflections—or “secondary imprints”—bouncing back to us from shiny objects in a distant space, such as a Christmas-tree ornament, a silver balloon, or a foil potato-chip bag, can be pieced together again to reveal what was inside the room at the time the image was taken. Imagine this on the scale of the cosmos, and you begin to find at least conceptual overlaps between these two technologies.

“The universe is really a shadow theater in which the galaxies are the protagonists, and the CMB is the backlight,” a cosmologist named Emmanuel Schaan explains to Quanta, describing a type of research known as “backlight science.” (Quanta also links to a “Backlight Mission” spacecraft initiative, dedicated to “backlight astronomy,” which, as per all of the above, sounds cinematographic in nature: imaging distant objects indirectly through their shadows and reflections.)

AUDIOGRAPHY

Continuing the ambient music theme of the last few posts, I thought I’d link a few tracks by “investigative sound artist” Jeff Surak. Much of his output can be abrasive—in the vein of what I might call proof-of-concept ambient, i.e. ambient music the technical creation of which is often more interesting than the final aesthetic results—but quieter tracks, such as the modular, staircase rhythms of “spaces that are filled” or the silvery luminescence of “love and production” (which, to my mind, is what a “backlight” cosmic mapping survey might sound like), or the dawn chorus collage of horns in “slaughter on 10th street,” are great places to start.

As a bonus track, I recently rediscovered the eerie darkness of “Gold Painted House” by David Tagg, and recommend giving it a few plays.

Till next time!