Notebooks, Shredders, and the Horror of Mistranscription

Personal notebooks vs. online writing, and some thoughts on analog horror

HOME FIRES BURNING

In an interview published yesterday morning, director Steven Soderbergh revealed that he recently burned 44 years’ worth of hand-written journals.

“I burned, a couple of months ago, 44 years [sic] worth of notebooks and journals,” he explained to Georg Szalai of The Hollywood Reporter. “I just felt I needed to dispense with the past. It was very cathartic. I would pick each one up and flip through it for a second to get a sense of when that was and would pick out a sentence or something, and then throw it into the fire. And it felt really good.”

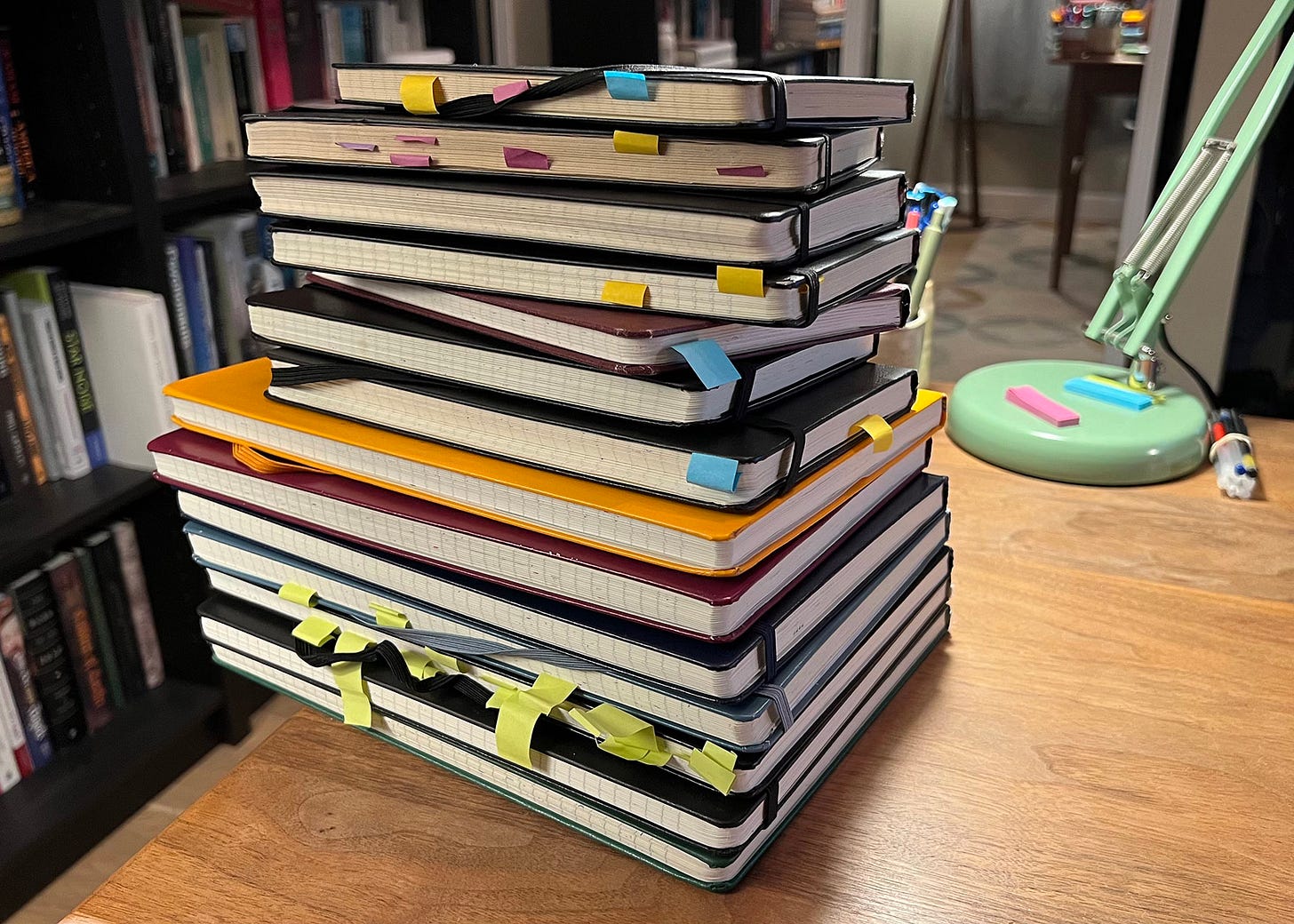

Image: With the exception of the yellow book, which I abandoned midway through, these are notebooks I have filled since the start of COVID, in 2020. These are a mix of Moleskines and Leuchtturms. The adhesive tags are for things I still want to type out, to use either in short fiction, in my newest book project, or in future posts. Leuchtturms are my current go-to notebooks; I prefer hardcover binding with lined paper. I used to prefer paperback binding and blank paper; before that, I preferred very small notebooks with 5x5 gridded paper. I could go on and on about pens, meanwhile, but will save that for another day…

Having purposefully destroyed dozens of notebooks over the course of my own life—not by fire, but with patience and a home shredder—I am, perhaps ominously, now sitting next to a growing stack of notebooks I started filling around the beginning of the pandemic, in 2020. At the time, I still maintained a (somewhat) regular blog—a site called BLDGBLOG, about architecture in various contexts—but, for a variety of reasons, I almost entirely abandoned writing online and returned instead to keeping private notebooks. A lot of notebooks.

Ironically, I gave up regular handwriting like this two decades ago, when I first launched BLDGBLOG. That decision was made precisely in favor of writing publicly—that is, sharing and posting my thoughts online—following the realization that carrying all this paper around with me, full of notes no one else will ever read, was a fool’s errand.

But here we are. After four years of voluminous daily notebooks, I’ve come around again to the realization that writing for an audience larger than myself—even if it’s just one other person—is more worthwhile than filling up yet another Leuchtturm, my current notebook of choice, or yet another Moleskine, yet another Shinola, the notebooks I previously favored.

For me, then, the main question posed by that Soderbergh interview was: will I shred all of these notebooks in the next ten or twenty years? Probably, yes; in fact, I’m almost certain of it.

Nevertheless, I’ve now spent four years depressurizing from endless social media bullshit and I don’t regret it—even if I do now have a stack of paper no one else will read, nearly a foot high, that I’ll be hauling around until such time as an office shredder, once again, beckons.

ANALOG HORROR, MISTRANSCRIPTION, AND ERRANT RECORDINGS

In an essay posted back in May, a writer named Kerwin Fjøl wrote about where the “horror” in analog horror really comes from.

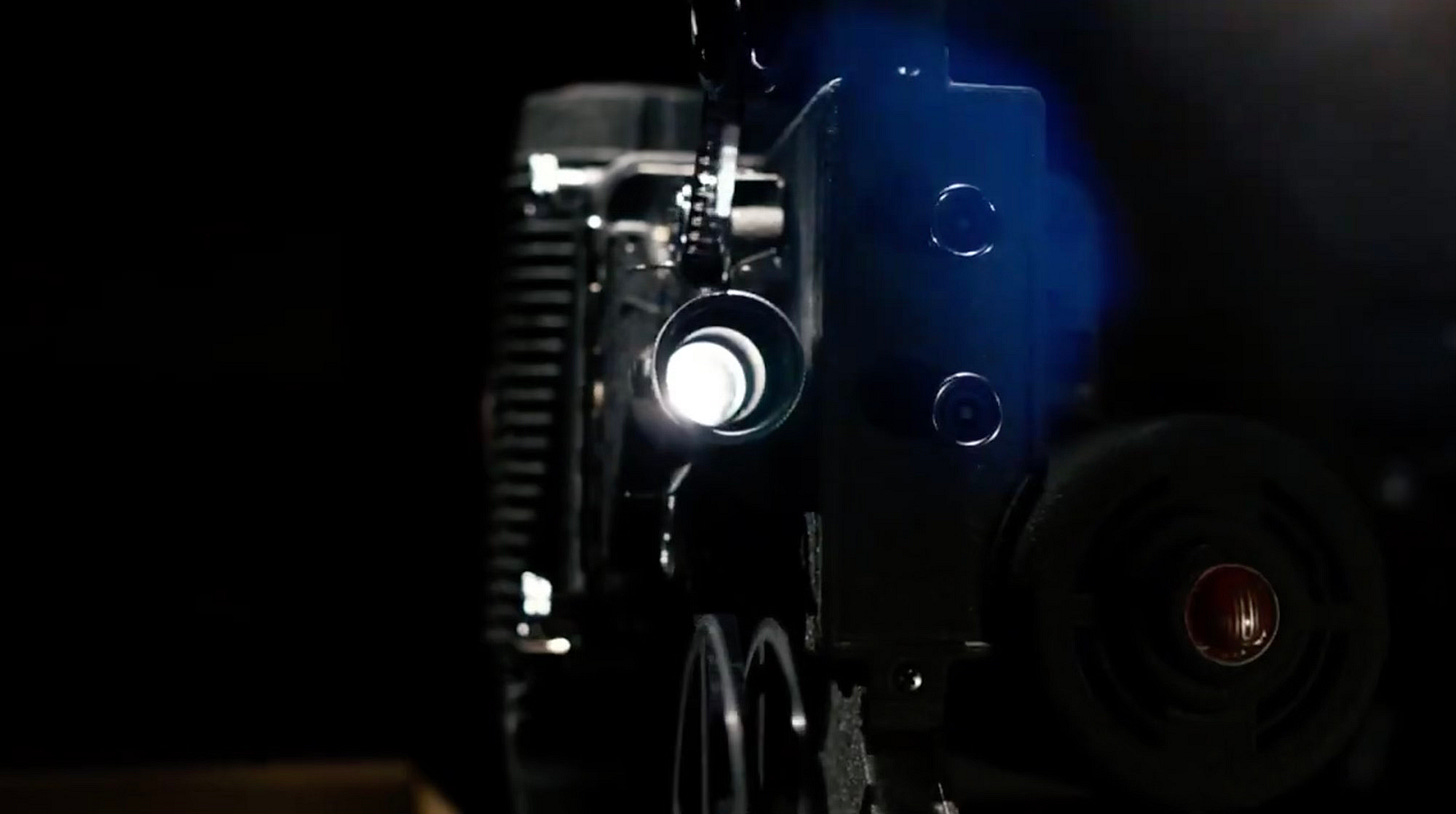

The term itself generally refers to a sub-genre in which a mechanism of analog recording or broadcast—say, a reel-to-reel tape machine, a vinyl record player, a VHS camera, a terrestrial TV set, an AM/FM radio, a dial-up computer modem, sometimes a simple children’s toy, like a Ouija Board, a music box, or a Speak & Spell—is discovered to contain, or has been used to reveal, a horrifying secret. Unsettling moments of vocalization, noise, and visual interference often begin, suggesting that something inhuman has been accidentally captured, if not actively conjured, by that tool or technology.

In all cases, analog horror is about a technology of inscription—a recording device in and of itself—that acts a bit like a haunted portal, opening our senses to something horrifying, here, present, often in the very room with us, but of which we were previously unaware.

IMAGES: From Evil Dead 2 (1987), directed by Sam Raimi.

Fjøl’s central point seems to be that it has become de rigueur today for critics to claim that analog technologies invoke horror because of nostalgia: that Super 8 film-stock or VHS tapes are inherently creepy because they are obsolete artifacts from another era.

A “big problem with this argument,” Fjøl responds, “is that analog distortion has been used for horror long before analog media became outdated. One of the first movies I can think of in which TV static was used to unsettling effect was Poltergeist (1983), in the scene where the static comes on as the TV stations have gone off the air, some ghosts come out of it, and the little girl says, ‘They’re here.’ No one was nostalgic for TV static then, because it was a regular part of people’s everyday viewing experience. Additionally, The Ring and The Blair Witch Project both came out at a time in which people were still regularly renting and purchasing VHS tapes. So it clearly isn’t the ‘pastness’ of analog media that matters here, as much as people may want to insist upon it.”

IMAGES: From Sinister (2012), directed by Scott Derrickson.

The horror in analog horror, Fjøl writes, does not require nostalgia at all: “old records, VHS tapes, and other antiquated media instead function as a reminder of something more basic and more important: namely, that despite our best attempts to create a world of absolute certainty and clarity, and our overwhelming faith in digital technology as the means with which to do it, there’s still an inalienable primordial chthonic force lurking underneath the surface, underneath every piece of information we take in.” It’s the insurgency of the material: a radically inhuman presence has crept into our picture of the world, contaminating our representations from below.

This statement overlaps with media critic Douglas Kahn’s book Earth Sound Earth Signal. Kahn argues that previously unknown sources of noise—including radio waves from space, resembling voices from nowhere—have always supplied an eerie sheen to modern communication technologies. The radio, the telegraph, the telephone: these now-everyday tools all once had the air of liminal devices or supernatural tools, invisibly tapping into telluric and cosmic energies. As Kahn memorably writes, “receiving radio may mean that someone is listening but not always that anyone is sending.” You are mistaking noise for signal. What you think are deliberate transmissions might, instead, be phantom radio waves from distant stars or the hiss and flash of a nearby lightning storm. No one is “sending.”

For both Kahn and Fjøl, then, inscription technologies have inherent, uncanny implications, and these are foundational to what we call analog horror: our tools, suspiciously over-sensitive and operating beyond our control, have revealed the maddening presence of inhuman things. Something beyond representation—beyond our powers of technical inscription—has made its uncanny presence known.

But it’s this notion of horror that still gets to me. Why horror at all? Why not ecstasy, revelation, or awe?

Consider a scenario in which someone sets out to record an event—a backyard party or a camping trip, or perhaps just a decluttering session in a badly-lit basement—only to see something else in the subsequent documentation. Something else had been going on that entire time and it was only through this recording that they were able to discover it.

While this scenario is often played for horror—a pale face seen staring back at us from the shadows—there is no reason it needs to be. Indeed, this specific trope is often used as the central hermeneutic premise of popular crime fiction, not to mention of much sci-fi and of many spy/espionage thrillers. Think of Blow Up, for example, or its later homage, Blow Out, or The Conversation—or even the parade photos from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo—canonical examples of recording technologies assuming a key role in the revelation of unseen conspiracies. Somewhere in this depiction of an event is evidence of forces that exceed that event. This is as much gnosticism as it is horror.

This is the premise of spy fiction and analog horror—but also of any belief in a sanctified world manipulated from behind the scenes by theological powers. In all of these, revelation relies on accidental hermeneutics: a tool of inscription or recording has captured more than we thought present in a particular scene or event, and now we have to interpret that event’s deeper meaning.

It seems reasonable to suggest, then, that the horror in analog horror is an epistemological one: it is an uneasiness some might feel, or uncanny discomfort, with the idea that we cannot represent the world in its totality. There will always be more—there will always be a surplus, a remainder, an outside, an excess—creeping into scenes we thought we had fully captured or controlled.

Analog horror, then, is when a model we have built for ourselves frighteningly deviates from—or outright betrays, mocks, inverts, humiliates, or, to put this in Biblical terms, becomes adversarial to—its source material. It is when we recoil from a revelation that our world cannot be captured accurately, that our representations of that world—think of so-called “voodoo dolls” or “The Picture of Dorian Gray”—have awoken or obtained adversarial agency.

THE PATTERN WINS BY LOSING YOU

In my previous post, I wrote about the ambient music of Huerco S, including a side-project of his known as Loidis.

This week, I thought I’d highlight the modular, shifting, off-kilter rhythms of Bill Converse, where the beat stumbles around, shuffling through wounded time-signatures, accumulating density and pattern along the way. “Since moving to Texas in 1998,” his Bandcamp page explains, “he has experimented with analog techniques in varied studio bunkers. Early techno, noise, ambient, tape, and paranormal processing are all part of his uncanny sound palette.”

Tracks like “Beneath the Ice,” for example, are oddly punctuated loops that pirouette, stagger, and twirl. Or consider “30.26367, -97.77082,” “Between Electrons,” “Meditations/Industry,” or “Phantom Pain.” If you start listening at the wrong moment, or if you momentarily lose focus, it can be difficult to relocate where the loops were meant to begin.

Converse’s music makes an interesting companion to tracks by Hieroglyphic Being—an “ex-gigolo healing the world with house music,” as the Guardian wrote back in 2016—where acid-blurred strings and distorted steel-drum sounds squeal, warp, and overwhelm atop a fuzzy, insistent, lo-fi beat. See, for example, “The Way of the Tree of Life,” “Flexin 4 the Dome,” and “21 Ways,” or give a listen to the tracks featured on The Language of Strings Vol. 6 (such as track two).

I really enjoyed reading this and last week's post. The link between Analog Horror and the Ambient music notes is really, funnily, thrilling for me to read. This link between analog machines to create horror and the Ambient music zone where analog and digital machines are manipulated to create soundscapes that are somewhere between horror, joy, and relaxation is really great.

Two things this made me think of immediately after reading are things I've read by Robin Sloan. First is from his newsletter with notes about reactions to a story featuring a synthesizer. Then the story itself.

1. https://www.robinsloan.com/newsletters/sunshine-skyway/

2. https://brandnewbox.com/inthestacks/

Then a cool third thing I found while writing this comment... they printed a really interesting version of the story!

3. https://brandnewbox.com/notes/2022/12/heres-to-2023/

Then my own connection to all of these things.

Heading into pandemic and through it I became really interested in synths and looping music making machines purely for my own diversion so reading this weeks post was thrilling given that at many times in the past few years my desk has been cluttered with a "The Conversation"- esque looking set piece of synths, recording devices, wires, patch cables, speakers, tape decks, an ipod, microphones, and headsets where I would sit for hours during lock-down evenings creating my own soundscapes; all of which, at least to me, fit somewhere between an attempt at expressing, creating, capturing and trying to insert the horrific or even possibly joyful moments into, at best, attempts at creating music and more to the point learning new things which is also joyful and at times full of horror.