Quantum Navigation, Books to Read, Ambient Music

Some recommendations for a mid-summer break.

Using a city’s underground transportation network as a venue for clandestine scientific experiments is a premise I can easily get behind. Recall architect Lebbeus Woods’s pitch for “Underground Berlin,” a never-produced film that would have been set against a backdrop of seismic-research labs in the Berlin U-Bahn network, where “scientists and technicians are working on a project for the government to analyze and harness the tremendous, limitless geological forces active in the earth.”

These “subversive scientists,” Woods wrote in his description of the unmade film, “believed—rather mystically—that only by a mastery of primordial earth forces could the barbarism of the surface culture above be overcome. Over the years, as history played itself out above, they developed structures, instruments and machines tuned to seismic, magnetic and gravitational forces that became their houses and laboratories, the better to come into harmony with, then gain mastery over the immense earth forces.” The underground system becomes both host and instrument, setting and tool. Woods’s treatment is worth reading in full.

While not quite an example of alt-seismic planetary mysticism, the Guardian reported last week that physicists in London have been using the city’s Underground trains as a venue for testing quantum navigational devices. These are extremely powerful tools of spatial orientation that do not require external signals to mark and record their location. “Tube train tunnels are ideal for this task,” we read, “and London Underground stands to gain from new quantum sensors that would remove the need for the hundreds of miles of cabling that is currently installed to track the location of the 540 trains that zip below the capital at peak times.”

I would love to see cartographic visualizations of the subsequent experiment, not just in traditional plan view, but volumetrically, as the devices rise, sink, and turn below the city, like quantum machine-whales migrating beneath people’s homes and offices. (Thanks to Wayne C. for the tip!)

NIGHTSTAND | WHAT WE’RE READING

I’m heading into the summer with a major backlog of books piled up on my nightstand (and office desk and bedroom shelves and kitchen table…), so I thought I’d call out a handful of titles here. Many more to come!

Silt Sand Slurry: Dredging, Sediment, and the Worlds We Are Making by Rob Holmes, Brett Milligan, and Gena Wirth (Applied Research & Design) — The folks behind Dredgefest have documented their decade-long research expedition into all things muddy and dredgeful with Silt Sand Slurry. Dredging exhumes the sodden remains of broken landscapes by scraping river bottoms, ocean floors, and lakebeds of their sediment, which is then often dumped elsewhere to shape harbors, levees, artificial islands, silt-containment cells, and more. With Silt Sand Slurry, dredge—a form of terrestrial-scale 3D-printing, or what the authors also call “designing with sediment”—finally receives the attention it deserves in the context of landscape engineering, infrastructural speculation, and ecosystem repair. Congrats to the whole crew for putting this together!

Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush (Milkweed Editions) — I really enjoyed this journalistic account of American flooding and the specificity with which author Elizabeth Rush assembled it. She says quite clearly that Rising was not intended as an all-encompassing book about the effects of climate change, but was instead shaped around a simple request: to “ask residents to tell me their flood stories.” Grounding the planetary-scale experience of rising sea levels through first-person interviews with flood survivors, filled with stories of emergency phone calls, missing family members, pets trapped in flooding neighborhoods, entire streets becoming rivers, and vast swaths of Louisiana—even, as Rush shows, parts of Staten Island—turning into seabed gives an urgency to subject matter that might otherwise seem too large-scale and abstract to elicit a response. The catastrophes of climate change, while globally ubiquitous, will all be experienced locally. (Rush’s new book, The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth is also on my list for 2024.)

Time and Its Adversaries in the Seleucid Empire by Paul J. Kosmin (Belknap Press) — I’ve enjoyed following Paul J. Kosmin’s research agenda from afar, including his forthcoming book The Ancient Shore, which explores “the influence of the coast on the inner lives of the ancients: their political thought, scientific notions, artistic endeavors, and myths; their sense of wonder and of self.” Until that book’s release, in October 2024, check out Kosmin’s Time and Its Adversaries in the Seleucid Empire—the description alone is incredible. “In the aftermath of Alexander the Great's conquests, his successors, the Seleucid kings, ruled a vast territory stretching from Central Asia and Anatolia to the Persian Gulf. In 305 BCE, in a radical move to impose unity and regulate behavior, Seleucus I introduced a linear conception of time. Time would no longer restart with each new monarch. Instead, progressively numbered years—continuous and irreversible—became the de facto measure of historical duration.” But there’s a twist: “Some rebellious subjects, eager to resurrect their pre-Hellenic past, rejected this new approach and created apocalyptic time frames, predicting the total end of history.” Calendrical insurrectionaries!

English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains and Menageries by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan (Paul Mellon Centre) — The title alone here was irresistible for me, and the book itself is a satisfying look at British eccentricity, cultural landscape practices, and botanically-inspired architectural design. Note that Longstaffe-Gowan has a new book coming out later this year that’s already on my radar, called Lost Gardens of London. Looking forward to it.

The Folds of Olympus: Mountains in Ancient Greek and Roman Culture by Jason König (Princeton University Press) and Journeys to Heaven and Hell: Tours of the Afterlife in the Early Christian Tradition by Bart D. Ehrman (Yale University Press). Otherwise unrelated, these books both survey extreme landscapes and their symbolic/religious meanings throughout human history—or what König calls “human engagement with the earth’s surface” and its role in shaping theological beliefs and practices. Expect remote mountain peaks, deep forest caves, and pristine meadows alike, with immense poetic resonance in myth and folklore.

Faux Mountains by Michael Jakob (ORO Editions) — Jakob’s slender book catalogs an exhibition he curated at Harvard several years ago, exploring examples of landforms that are actually works of architecture, or architecture disguised as geology. Imperial tombs, folk festivals, garden follies, zoo habitats, Disneyland, and more. (Thanks again to Wayne C. for the tip!)

The Ascent by Stefan Hertmans (Pantheon) — I’ve come to admire Stefan Hertmans’s fiction over the past few years, including two earlier novels translated into English, War & Turpentine and The Convert. They are novels in a fairly specific sense: Hertmans is, indeed, telling the stories of historical figures, whose full lives and existence he did not himself experience, and he is thus describing things he did not witness first-hand, which is, almost by definition, fiction. But, for me, his books read less like novels than as exceptionally engaging, long-form articles describing Hertmans’s personal attempt as a writer to shape and resolve a complicated research agenda. The Ascent has the benefit of a strong architectural frame for its narrative. The book is structured around Hertmans’s initial real-estate tour and subsequent purchase of an old building in Ghent, Belgium; throughout the ensuing story, the building’s rooms, halls, doors, and stairs all lead to new historical scenes in the lives of the people who previously lived there, opening onto a world of Nazi collaborators, youthful political naïveté, marital betrayal, European darkness, and more.

Liquid Snakes by Stephen Kearse (Soft Skull) — Liquid Snakes, a novel I had the pleasure of blurbing back in 2023, is soon out in paperback! Author Stephen Kearse—an unusually perceptive critic of everything from hip-hop and heist films to noir fiction—has written a novel that is part epidemiological whodunnit, part sci-fi, part bizarro-internet-coffee-biochemical-future-terrorist thriller that rides on equal tides of humor and outrage. Black students begin disappearing in sinkhole-like events; a radicalized social media account and a local coffeeshop owner reveal unsettling overlaps; and CDC investigators are left struggling to connect impulses toward self-destruction with black-market compounds, no pun intended—drugs that promise self-renewal (and erasure and martyrdom and revenge). The humor is as acidic as the book’s central, fictional substance: “Vincent swiveled away from his computer and examined the massive artwork. For every Atlanta voter his advisors told him mattered, there was at least one head from their personal Mount Rushmore: Barack Obama, Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King, Samuel Cathy, Monica Kaufman, André Benjamin, Ciara Wilson, Steve Harvey, Mike Lazzo, Stacey Abrams, Tayari Jones, Radric Davis, Stan Kasten, Michael Vick. It was the tackiest, most incomprehensible mural he’d ever seen...” (I also had the pleasure of publishing Kearse’s fantastic short story, “Retriever,” about the end of the 2nd Amendment, which was promptly optioned for TV.) Preorder a copy for its release on August 13th.

Monolithic Undertow: In Search of Sonic Oblivion by Harry Sword (Third Man Books) — Sword’s book is a history and aesthetic of drones in music, from ragas to black metal to ’90s rave to Godflesh (here’s their immense 1989 grindcore track “Streetcleaner”) and Coil. The book covers black holes, Dionysian rituals, sonic weaponry, neolithic burial cairns, mysterious atmospheric whispers, prog rock, and “the power of sound to induce feelings of terror, raw or unease.” Describing the impulse behind the book, Sword writes that, “while velocity in music is readily associated with unrest, the left-hand path—slowly-moving hypnotic sound—is a road far less traveled, at least critically.” Speaking of Godflesh, I’m reminded of their old t-shirt, describing their music as an “avalanche on pause,” as good a description of a drone as any.

Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains by Alexa Hagerty (Crown) — Alexa Hagerty is an anthropologist who, in Still Life with Bones, has documented her time working in post-conflict Guatemala and Argentina, examining the dead, locating the disappeared, and exhuming the victims of state violence. In Hagerty’s own words, the book “explores the matter and meaning of bones: how they are marked by violence and tested in genetic labs. It is also about how bones are always joined to grief, memory, and ritual.” Wonderfully written, somber, and filled with scenes of cinematic clarity, the book visits morgues, private homes, and unmarked graves to tell the story of families torn apart by political oppression. In a book of memorable take-aways, one stood out: “Exhumation never brings back the beloved,” Hagerty writes—though it does bring back a modicum of emotional agency for the affected, as well as a long-shot opportunity for political justice in a wounded society. (This might be a somewhat strange recommendation, I admit—or one that risks sounding flippant or dismissive of the real-world stakes of Hagerty’s book—but the recent novel Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez makes an eerie companion to Still Life with Bones. Enriquez’s supernatural horror story is a surprisingly beautiful novel of black magic, demonic self-sacrifice, Argentine aristocrats, and family obligations set against a backdrop of militarized political oppression.)

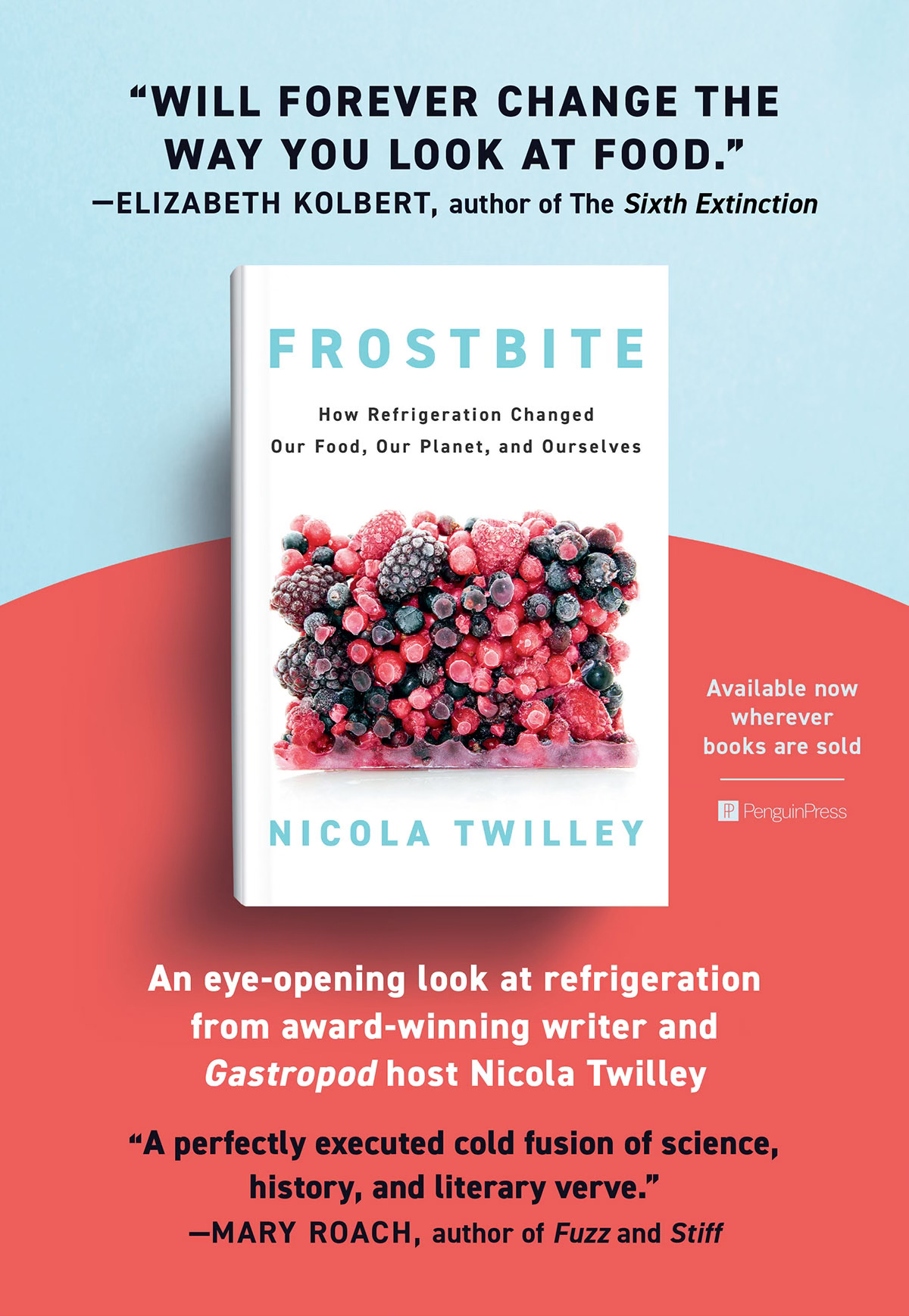

Finally, I am unusually excited about this next book, as I’ve watched from behind the scenes for several years now as the research and reporting have come together. Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves by my wife, Nicola Twilley (Penguin Press), comes out Tuesday, June 25th, and is absolutely vital for any conversation today about food, energy, health, and urban development. In it, Nicky shows that using artificially-generated cold to preserve our food supply has changed our cities, our bodies, our planet’s atmosphere, the flavors of our fruits and vegetables, our financial markets, and even the lyrics of the song “America the Beautiful.”

The New York Times lauds the book as “engrossing” and “hard to put down.” In a starred review, Kirkus says that Frostbite is “oddly fascinating… a literate treat.” In another starred review, Publishers Weekly calls the book “a revelatory deep dive into refrigeration’s past and present… a brilliant synthesis.”

Nicky has dominated the refrigeration beat for more than a decade and her book has the receipts, from first-person visits to cheese caves in Missouri, banana-ripening rooms in the Bronx, and farms in Rwanda, to original reporting on the African-American inventor behind refrigerated trucks, the woman who lived inside a cargo container for nearly ten years to study the cold chain from the inside, a Chinese frozen-dumpling billionaire, and the entrepreneurs and innovators around the world today looking to disrupt, redirect, and climate-proof the future of food preservation. One amazing line strikes me every time I read it: as refrigerated foods were first hitting the American market, arriving on the plates of suspicious diners, a newspaper in Buffalo ran the headline, THERE IS NO DEATH, ONLY COLD STORAGE.

Because I got to tag along on some of the reporting trips, I have personally experienced the strange architectural interiors of the global cold chain, including metal vats the size of missile silos, inside of which swirled vortices of discolored orange-juice concentrate, and limestone mines that have since been converted into underground vaults filled with frozen pizza.

The fact that Frostbite ends with Ragnarök is a sign that the book is about far more than just fresh eggs, fad diets, and cold beer. It’s a thrill to see this finally out in the world and I encourage everyone to take a look!

AUDIOLOGY | WHAT WE’RE LISTENING TO

I’m a longtime fan of Huerco S’s ambient tracks—even if others might not necessarily use that term. Strange, shimmering, crystalline-metallic soundscapes made from loops and drum tracks, blurred and stretched, loosely layered, framed, and ticking overtop one another, his music is like watching faded-color filmloops through a lens of Scotch tape. Check out early tracks like the chiseled rhythms of “Quivira,” for example, a personal favorite of mine; the oddly sinister, mineralogical repetitions of “Marked for Life”; or the off-kilter, nursery-rhyme melodies of “Promises of Fertility.”

Huerco S also has some side-projects. Loidis, a pseudonym he has been using since roughly 2018, has a debut album coming out later this summer. Will it be good? I hope! But cue up a couple of dub-techno/ambient-house tracks from Loidis’s 2018 EP, such as “A Parade” or the epic, hypnotic, calming, awesome “The Floating World (& All Its Pleasures)” for a glimpse of what might be to come.

PS: If you like that, here’s a bonus ambient track: “Doggerland” by Ekolali, a rain-washed atmosphere of slowly-churning drums and ritualistic whorls of sound, like picking up a prehistoric AM radio signal broadcast from the depths of the North Sea.

OPTOMETRY | WHAT WE’RE LOOKING AT

To close out this post, I could link to any number of U.S. Library of Congress image sets, which are seemingly innumerable, but I’ll instead choose two.

First up are early-20th-century photos by Sergeĭ Mikhaĭlovich Prokudin-Gorskiĭ, taken at various sites around the Russian empire. The images are strangely layered digital composites, produced from glass negatives—some of which are shattered—almost all of which resemble avant-garde album art. See, for example, the Novyi Afon monastery (larger); “details of Milan cathedral” (larger); a whirl of swords in a weapons cabinet (larger); a simple haystack (larger); extraordinary “cornflowers in a sea of rye” (larger); or this related shot of an agricultural out-building amidst cornflowers (larger). There are hundreds more. (Interestingly, those particular images were all composited for the Library of Congress by none other than Blaise Agüera y Arcas, whose fantastic 2007 presentation of “PhotoSynth” technology showed that advanced computational photo-editing tools can achieve internet virality.)

Second, for design-history nerds, here are 300+ digital pages’ worth of advertising labels from the 1870-1880s, an incredible archive of early trademarks, logotypes, and brand identities for everything from chemical paints to condensed milk, from pine shingles and lubricating oils to cement, by way of bourbon, fountain pens, chewing tobacco, cigars, and much, much more (mustard, pickles, “jubilee twists”…). An early inventory of Americana and the American design imagination as told through popular products.